The Mozart Effect

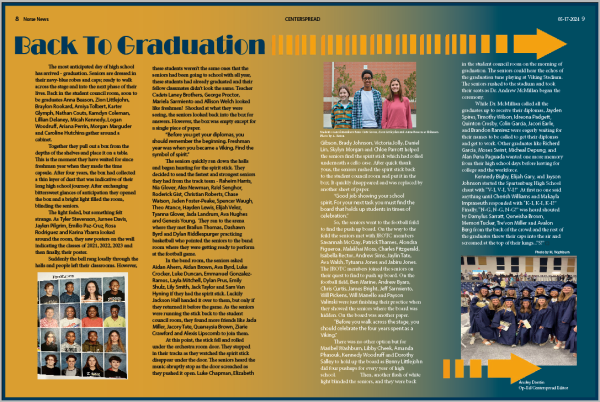

November 11, 2020

Contrary to popular belief, classical music doesn’t make you smarter. This idea, also known as the “Mozart Effect,” gained attention after the prestigious scientific journal Nature published a paper in 1993. A study led by psychologist Frances Rauscher found that 36 college students who listened to a sonata by Mozart for ten minutes scored approximately eight points higher on spatial intelligence tests than those who listened to relaxation instructions or silence.

In an interview with npr.org, Rauscher emphasized that the test given to the participants only measured one specific aspect of intelligence, not general intelligence. The cognitive benefits produced by listening to the classical music only lasted 10 to 15 minutes.

When Rauscher’s study was published, she did not expect others to be very interested in her findings. However, she received a call from Associated Press, who wanted to publish a story on the Mozart Effect. Once the story was printed, the Mozart Effect was everywhere.

Rauscher’s findings started being distorted. The results of her study were generalized, and myths about the benefits of playing classical music for children were spread. Thousands of parents played classical music for their children, in hopes that it would increase their intelligence. In 1998, the governor of Georgia even tried to use funds from the state budget to purchase a classical tape or CD for every newborn baby in the state. Rauscher theorizes that her study received such a widespread response because parents want to do everything they can for their children and Americans are fond of self-improvement and quick solutions.

According to bbc.com, in 2006, a similar study was conducted in Britain. Eight thousand children listened to either 10 minutes of Mozart’s String Quintet in D Major, a discussion about the experiment, or a series of three songs by Blur, a Britpop band. They found that music improved the children’s ability to predict paper shapes. The children who listened to Mozart did well, but the children who listened to pop music did even better.

This study suggests that the “Mozart Effect” isn’t really about Mozart – it’s about enjoyment. If you hate Mozart, you aren’t going to experience a Mozart Effect. If Beyoncé is more your speed, chances are you will find a Beyoncé Effect.

So, the next time you have to do some imaginary origami, listening to your favorite music may help. Other cognitively arousing activities, such as drinking coffee or stretching, are also likely to help.

If you listen to music while studying, it can put you in a better mood, which will increase the level of effort you are willing to put in. However, if the music is too fast, loud, or has lots of words (like rap or hip-hop), it may be distracting. You can find playlists specifically designed for studying on music streaming services such as Amazon Music, Apple Music or Spotify.